Auschwitz

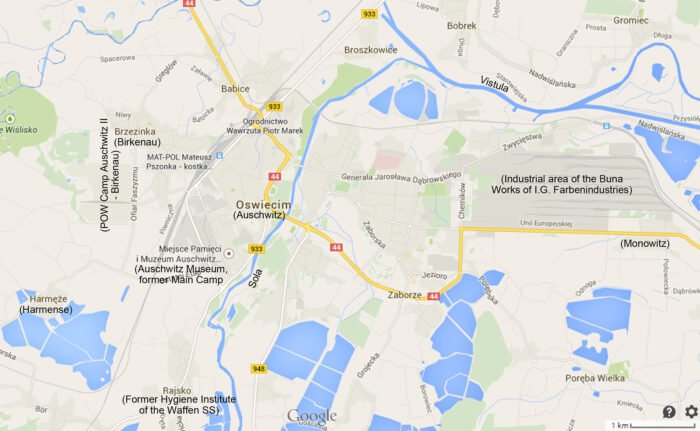

Google map of the region around Auschwitz, with black labels added.

The Polish town of Oświęcim (German: Auschwitz) lies in a valley at the Sola River near its confluence with the Vistula River. Already during the time of the Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy, a military barracks existed southwest of the town on the left bank of the Sola River. After World War One, the facility was taken over by the newly formed Polish armed forces, using it as artillery barracks and horse stables. After Poland’s defeat at the beginning of World War Two, the German Armed Forces took over the barracks.

Main Camp

During January and February 1940, the SS forces considered using these old barracks as a quarantine transit camp for Polish political prisoners, eventually to be sent to other camps. Due to lack of any sanitary installations, the facility was initially rejected. A change of mind followed in late February after suggesting some major upgrades. These were ordered in April, with a first detailed cost estimate following on 30 April 1940, listing numerous items to be constructed, such as: kitchen, laundry, water supply system, inmate bath, delousing facility. This facility would later be called Auschwitz Main Camp (German: Stammlager).

It is in this camp that the first gassing of inmates using Zyklon B is said to have occurred in late summer of 1941. This camp also saw the erection of cremation furnaces in a former munitions bunker, which was renamed to Crematorium I or “old crematorium,” to set it apart from the new cremation facilities later built at Birkenau. The morgue of this old crematorium is said to have been misused for the mass-murder of inmates between late 1941 and early 1942. For a more detailed description of this camp, see its dedicated entry.

Birkenau

On 26 October 1941, the Auschwitz camp administration received a phone call informing them that the Berlin headquarters of the SS planned to set up near Auschwitz a separate PoW camp for some 60,000 Soviet PoWs, which would be an integral part of the Auschwitz Camp. The planned capacity was increased over time, and reached a maximum of 200,000 in September 1942, although that figure was never reached.

Planning and construction of the camp started immediately near the village of Brzezinka (German: Birkenau) two miles west of the town of Oświęcim. However, except for a few thousand PoWs arriving at Auschwitz in October 1941, the large wave of Soviet PoWs never arrived, so the camp’s function changed from a PoW camp to a transit camp and forced-labor camp for Jews deported from numerous European countries.

On 22 November 1943, the PoW camp Auschwitz-Birkenau was separated from the Auschwitz Main Camp (then renamed to Auschwitz I) and became an independent concentration camp called Auschwitz II. However, on 25 November 1944, the Birkenau Camp lost its independence again, and was reintegrated in what was then simply called Auschwitz Concentration Camp.

For a more detailed description of this camp, see its dedicated entry.

Monowitz

Right from the beginning of the Auschwitz Camp’s existence, so-call subcamps or satellite camps were established in its immediate vicinity as well as in the wider region. These camps served to lodge forced-labor inmates close to their workplace, which included various mining, manufacturing and farming enterprises. At its peak, there were 48 satellite camps attached to the Auschwitz camp complex. The larger and best-known among them were the camps near the villages of Monowitz, Harmense and Rajsko. The Monowitz Camp was by far the largest among them, accommodating thousands of inmates meant to work at the nearby BUNA plant of the IG Farbenindustrie. The Harmense Camp was agricultural in nature, whereas Rajsko housed the southwestern branch of the SS Hygiene Institute as well as a plant-breeding facility. On 22 November 1943, all satellite camps near Auschwitz were separated from the Auschwitz Main Camp and became an independent concentration camp called Auschwitz III, with the headquarters at the Monowitz Camp. On 25 November 1944, the name was changed to Monowitz Concentration Camp. For a more detailed description of this camp, see its dedicated entry.

Death-Toll Propaganda

The first exaggerated death-toll figure that gained international attention was spread by the War Refugee Board Report, published in late 1944. It contained a mendacious essay by Rudolf Vrba written in May 1944, in which he claimed that, between April 1942 and April 1944, 1,765,000 inmates had died, implying that many more had died throughout the camp’s entire history.

The next notable event was a report issued by the Soviet Union after the Red Army had conquered the camp. The new figure was now four million victims. Not satisfied with this, the Polish court which tried former staff members of the Auschwitz Camp set the new mark at some five to five and a half million victims in 1947. There were other, higher figures bandied about right after the war, but they hardly received any attention (see the table at the end of this entry).

Several years after the war, after the hysterical propaganda dust had settled, the orthodoxy split into two schools. The western school of orthodox Holocaust scholars opined that the Auschwitz death toll was lower than the Soviet figure, but disagreed on the details. Their numbers ranged from just under a million (Reitlinger) up to three and a half million (Yehuda Bauer). Eastern scholars, on the other hand, had to comply with the Soviet four-million doctrine or suffer the consequences.

Many left-leaning western journalists and ideologues ignored the more-cautious numbers of western historians, and eagerly parroted the Soviet propaganda figure. Hence, the four million could often be heard in the West as well.

Since 1995: The new memorial plaque at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial.

Since 1995: The new memorial plaque at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial.This schism was overcome only when the Soviet Union crumbled. In fact, it was Jews who started complaining in 1990. They accused the Poles of having rigged the numbers to make themselves look like the primary victims. They simply added to the more than one million Jews deported to Auschwitz two million Poles and other nationals. But most of them had been invented. Jews accused the Poles of “minimizing the Holocaust” by exaggerating the Auschwitz death toll. Yes: minimizing through exaggeration! They also demanded the primacy of their victimhood, as anything else would minimize their suffering. A commission was formed, which decided that two and a half million invented non-Jewish victims had to be removed. The old four-million memorial plaques were replaced with new ones commemorating the loss of 1.5 million lives – 90% of them Jews.

Leftist scholars were caught with their pants down. They admitted publicly that they had been lying about the Auschwitz death toll for decades, knowing full well that it was untrue. But they begged forgiveness, because they had done it for a good, anti-fascist cause. Wácław Długoborski, for decades the Auschwitz Museum’s top historian under communist rule, excused his decade-long lies with the fact that “a prohibition against casting doubt upon the figure of 4 million killed was in force.” He forgot to mention that this prohibition was only replaced with a new one a little later. Contesting the current orthodox narrative is now not just prohibited, it is actually a crime in Poland – and most other European countries. (See the entry on censorship.)

They lied in the past, they are compelled to lie now, and they will keep lying in the future – until all censorship laws have been rescinded, special statuses for minority groups have been revoked, and freedom and fair play finally reign.

| No of Victims | Source (for exact references, see Faurisson 2003) | |

|---|---|---|

| 9,000,000 | French documentary film Nuit et Brouillard (1955) | |

| 8,000,000 | French investigative authority (Aroneanu 1945, pp. 7, 196) | |

| 7,000,000 | Filip Friedman (1946, p. 14) | |

| 6,000,000 | Tibère Kremer (1951) | |

| 5–5,500,000 | Krakow Auschwitz trial (1947), Le Monde (1978) | |

| 4,000,000 | Soviet document at the IMT | |

| 3,000,000 | David Susskind (1986); Heritage (1993) | |

| 2,500,000 | Rudolf Vrba, aka Walter Rosenberg, Eichmann Trial (1961) | |

| 1,5–3,500,000 | Historian Yehuda Bauer (1982, p. 215) | |

| 2,000,000 | Historians Poliakov (1951), Wellers (1973), Dawidowicz (1975) | |

| 1,600,000 | Historian Yehuda Bauer (1989) | |

| 1,500,000 | New memorial plaques in Auschwitz | |

| 1,471,595 | Historian Georges Wellers (1983) | |

| 1,250,000 | Historian Raul Hilberg (1961, 1985, 2003) | |

| 1,1–1,500,000 | Historians I. Gutman, Franciszek Piper (1994) | |

| 1,000,000 | J.‑C. Pressac (1989), Dictionnaire des noms propres (1992) | |

| 800–900,000 | Historian Gerald Reitlinger (1953 and later) | |

| 775–800,000 | Jean-Claude Pressac (1993) | |

| 630–710,000 | Jean-Claude Pressac (1994) | |

| 510,000 | Fritjof Meyer (2002) | |

| 135,500 | Carlo Mattogno (2023, Vol. 2, end of Chapter 3) | |

| See also http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auschwitz_concentration_camp#Death_toll | ||

The only number that is backed up by documental and material evidence is the last one in the table. Notably, it was presented by someone – Italian scholar Carlo Mattogno – who most certainly does not grovel before anyone’s altar, does not pay homage to anyone’s victim status, and does not get intimidated by governments threatening jail time in case of dissent.

(For more details, see Faurisson 2003; Rudolf 2023, pp. 123-128.)

You need to be a registered user, logged into your account, and your comment must comply with our Acceptable Use Policy, for your comment to get published. (Click here to log in or register.)